Rosetta Stone: How the Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Alphabet Was Deciphered by Champollion

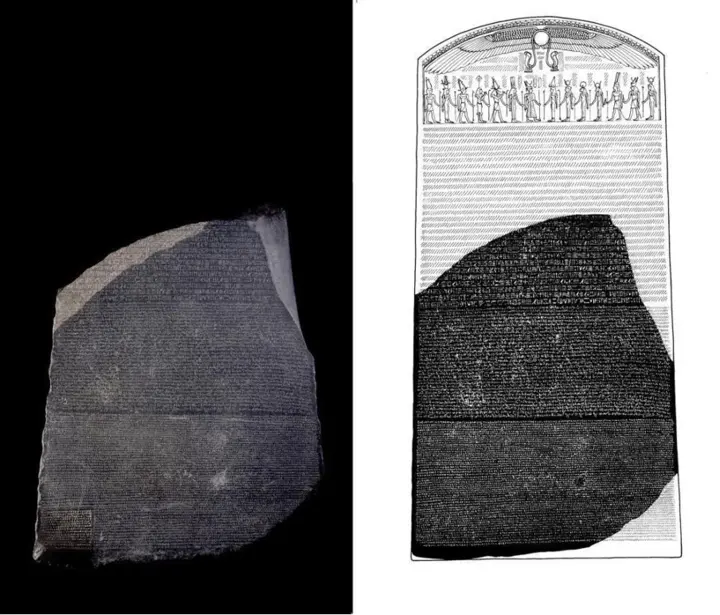

The Rosetta Stone, discovered in 1799 near the city of Rosetta in Egypt's Nile Delta, is part of a larger tablet inscribed with a decree issued in 196 BC during the Ptolemaic dynasty of Egypt. The decree was written in three texts: hieroglyphics, demotic (an abbreviated form of hieroglyphics), and ancient Greek, and was intended to be read and understood by the diverse population of ancient Egypt. The stone was carved during the Hellenistic period and is believed to have originally been displayed inside a temple.

Show key points

- The Rosetta Stone, discovered in Egypt in 1799, played a vital role in deciphering ancient Egyptian writing because it contained the same text in hieroglyphics, demotic, and ancient Greek.

- Jean-François Champollion, recognized as the father of Egyptology, was the first to fully decode Egyptian hieroglyphs using the clues provided by the Rosetta Stone.

- Hieroglyphics, the formal writing system of ancient Egypt, included phonetic symbols, logograms, and determinatives to convey both sound and meaning.

- ADVERTISEMENT

- The inscription on the Rosetta Stone is a decree from 196 BC issued to honor Ptolemy V, designed to be displayed in temples across Egypt in multiple languages for broader comprehension.

- Although British scholar Thomas Young made initial progress, it was Champollion who realized hieroglyphs combined phonetic and ideographic elements, revolutionizing their interpretation.

- After being transported to England in 1802, the Rosetta Stone has been housed in the British Museum and remains one of its most iconic and studied artifacts.

- The successful decipherment of hieroglyphs not only provided insights into ancient Egyptian civilization but also laid the groundwork for the modern field of Egyptology.

The Rosetta Stone is an irregularly shaped stone of black granite, 3 feet 9 inches (114 cm) long and 2 ft 4.5 inches (72 cm) wide, broken in ancient times. It contains 14 lines of hieroglyphics, 32 lines of demotic writing, and 54 lines of the ancient Greek language. The stone was found by a Frenchman named Bouchard or Bousard in August 1799.

Recommend

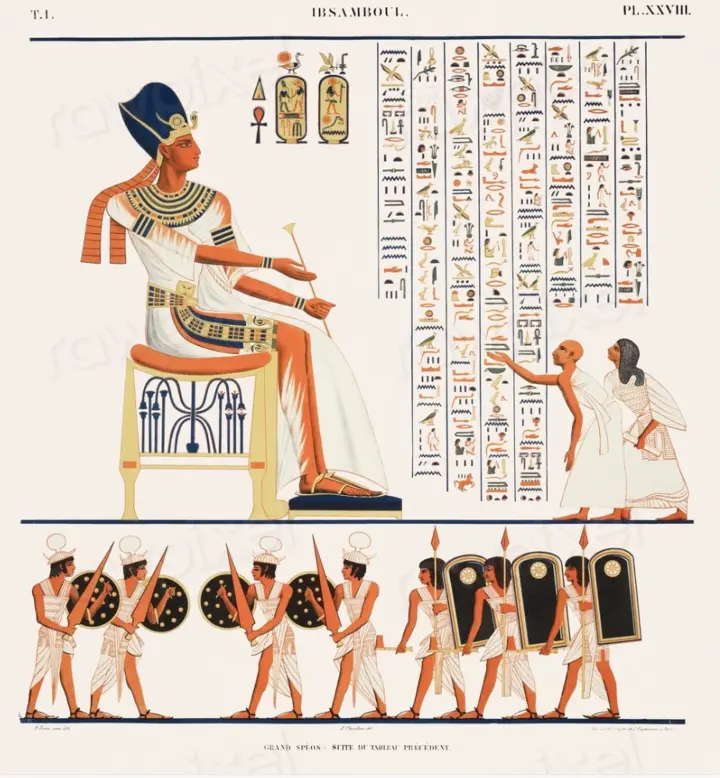

Hieroglyphic alphabet: a closer look

The hieroglyphic alphabet, the writing system used by the ancient Egyptians, is fascinating and complex. It appeared in Egypt around 3200 BC. It remained in use until Rome annexed Egypt. This ancient Egyptian writing system was complex and labor-intensive.

In hieroglyphics, there are three main types of glyphs. The first is phonetic glyphs, which include single letters that act like letters of the English alphabet. These roughly correspond to the 26 letters of the English alphabet. Masri also has signs for the sounds "sh" (as in "ship") and "ch" (as in "chip" and "charlie").

The second type of glyphs are logos, which are written characters representing a word, much like Chinese characters. These are the basic symbols used by the ancient Egyptians in their writings, but there are many others.

The third type of glyphs are delimiters, which are symbols that provide additional information about the meaning of a word. For example, a man selector can be added to a word to indicate that it refers to a male.

Only three percent of ancient Egyptians could read hieroglyphics. Hieroglyphs are pictorial representations of thoughts and sounds. They were used in buildings and tombs, and it is believed that the Egyptians first began developing this writing system around 3000 BC.

Hieroglyphs are written in rows or columns and can be read from left to right or from right to left. You can distinguish the direction in which the text will be read because human or animal characters always face the beginning of the line.

Jean-François Champollion: Father of Egyptology

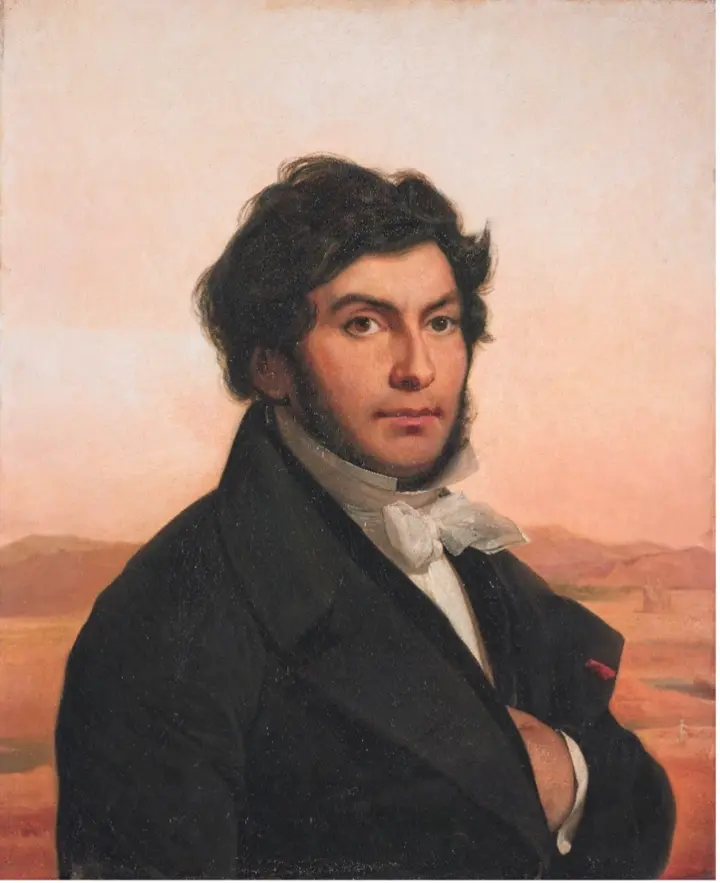

Jean-François Champollion, born on December 23, 1790 in Fijia, France, was a French jurisprudential scholar and orientalist, primarily known as the decipherer of Egyptian hieroglyphs and a founding figure in the field of Egyptology.

Champollion was a child prodigy in philology, presenting his first general research on deciphering demotic language in his late adolescence. In his youth, he became famous in scientific circles, and read Coptic, Ancient Greek, Latin, Hebrew and Arabic.

During the early nineteenth century, French culture experienced a period of "obsession with Egyptology", brought about by Napoleon's discoveries in Egypt during his campaign there (1798-1801), which also highlighted the trilingual Rosetta Stone. Scholars discussed the era of Egyptian civilization and the function and nature of hieroglyphics.

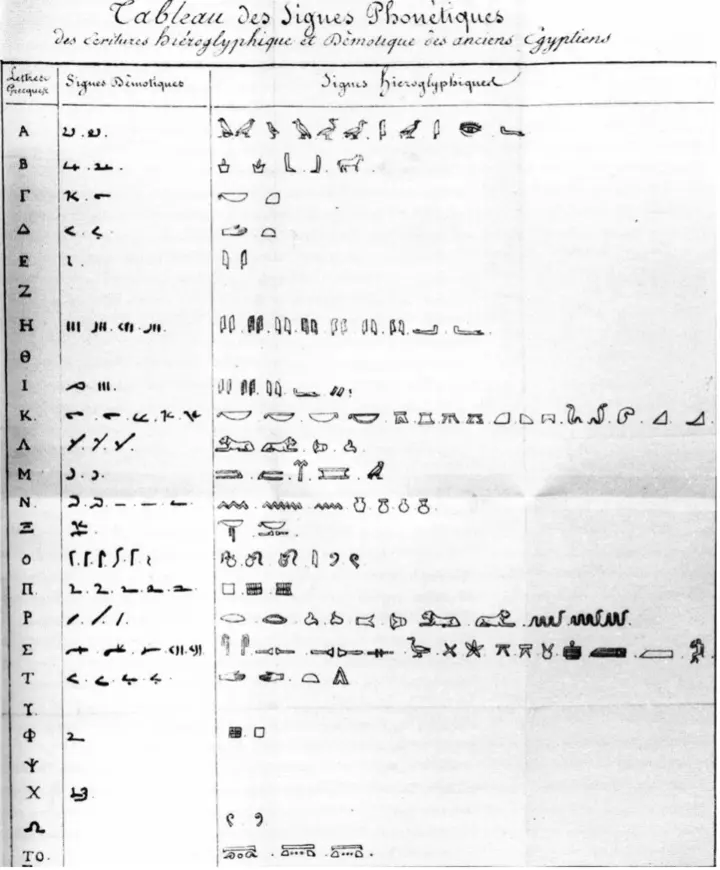

In 1820, Champollion seriously embarked on a project of deciphering hieroglyphics, and soon overshadowed the achievements of the British scientist Thomas Young, who made the first breakthrough in deciphering before 1819. In 1822, Champollion published his first breakthrough in deciphering hieroglyphics. Rosetta hieroglyphs show that the Egyptian writing system was a mixture of phonetic and ideographic signs.

Champollion lived through a period of political turmoil in France that constantly threatened to disrupt his research in various ways. His actions, which were sometimes reckless and reckless, did not help his cause. His connections with important political and scientific figures of the time, such as Joseph Fourier and Sylvestre de Sacy, helped him, although at some times he lived in exile from the scientific community.

Champollion became curator of the Egyptian collection at the Louvre (1826), undertook an archaeological expedition to Egypt (1828), and headed the department of Egyptian antiquities, created specifically for him, at the Collège de France (1831). In addition to his book on Egyptian grammar (1836–1841) and dictionary (1841–1843), his published works include Summary of the Hieroglyphic System of the Ancient Egyptians (1824; Introduction to the Hieroglyphic System of the Ancient Egyptians) and the Egyptian Pantheon; ou, the collection of mythological figures in ancient Egypt (incomplete, 1823–1825; the Egyptian Pantheon; or Collection of Mythological Figures in Ancient Egypt).

Champollion's work laid the foundation for the field of Egyptology and opened the door to understanding the rich history and culture of ancient Egypt.

Deciphering the Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Alphabet: Champollion's Discovery

The decipherment of the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic alphabet by Jean-François Champollion is one of the most important achievements in the field of Egyptology. The process was complex and required a deep understanding of various texts and languages.

Champollion's work began where Thomas Young, another scholar working on the Rosetta Stone, left off. Jung made great progress in understanding demotic writing and was able to recognize many phonetic signs. However, Jung believes that phonetic hieroglyphics were only used in writing non-Egyptian words.

Champollion, on the other hand, recognized that hieroglyphics are a combination of vocal and ideological elements. This was a major breakthrough in the decryption process. He compared the hieroglyphs in Ptolemy's cartouche with the other letters and realized that the same signs could be used to illustrate the names of different foreign rulers.

In the early twenties, Champollion published research on the decipherment of hieratic and hieroglyphic writing based on his study of the Rosetta Stone. He created a whole list of signs with Greek counterparts. His claims were initially met with skepticism and accusations that he had taken ideas from Jung without giving him credit. However, they gradually gained acceptance.

Champollion went on to learn the meanings of most of the phonetic hieroglyphs and establish many rules and vocabulary in the ancient Egyptian language. His work laid the foundation for the field of Egyptology and opened the door to understanding the rich history and culture of ancient Egypt.

What does the inscription actually say?

The inscription on the Rosetta Stone is a decree issued by the Council of Priests. It is one of a series that confirms the royal cult of 13-year-old Ptolemy V (opens in a new window) on the first anniversary of his coronation (in 196 BC). You can read the full translation here (opens in a new window).

According to the inscription on the stone, an identical copy of the declaration was to be placed in every large temple throughout Egypt. Whether this happened or not, but copies of the same bilingual three-text decree have now been found and can be seen in other museums. The Rosetta Stone is therefore one of many mass-produced paintings designed to widely disseminate a convention issued by the Council of Priests in 196 BC. In fact, the text on the stone is a copy of the prototype that was composed about a century ago in the third century BC. Only date and names have changed!

Where is he now?

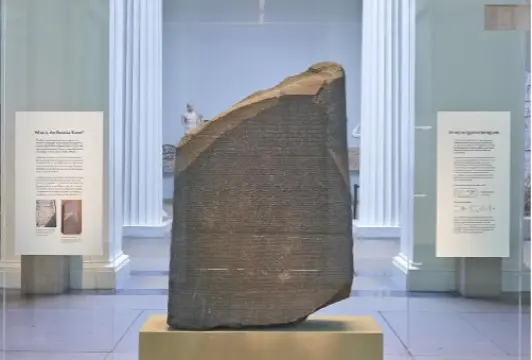

After the stone was shipped to England in February 1802, it was presented to the British Museum by George III in July of that year. The Rosetta Stone and other sculptures were placed in temporary structures on the museum grounds because the floors were not strong enough to withstand their weight. After petitioning parliament for the funds, the trustees began building a new gallery to house these collectibles.

The Rosetta Stone has been on display at the British Museum since 1802, with only one break. Towards the end of World War I, in 1917, when the museum was concerned about heavy bombing in London, they moved it to a safe place with other "important" portable objects. The iconic body spent the next two years at a station on the postal railroad 50 feet below the surface of Holborn.

Between October 13, 2022 and February 19, 2023, you can see the Rosetta Stone along with other objects that helped scientists decipher hieroglyphs in our special exhibition, Hieroglyphics: The Conquest of Ancient Egypt. You can also touch a replica of the Rosetta Stone in Room 1 (Enlightenment Gallery) and visit it remotely on Google Street View

The decipherment of the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic alphabet by Jean-François Champollion, with the help of the Rosetta Stone, marked a milestone in the study of ancient civilizations. He not only unlocked the secrets of ancient Egypt, but also paved the way for further exploration and understanding of other ancient texts. Today, thanks to the works of Champollion and the discovery of the Rosetta Stone, we can appreciate the richness and complexity of ancient Egyptian civilization in a way that was not possible for more than a thousand years.